Science Report for October 8th

HOW GYPSUM LINKS THE MARS DESERT RESEARCH STATION TO MARS

Jonathan Clarke

Gypsum at the Mars Desert Research Station

Gypsum is hydrated calcium sulphate – CaS04.2H20. It is a common mineral found in salt lakes and coastal lagoons on Earth, and also in veins, hydrothermal systems, weathered rocks, and desert soils. Its presence in soils and sediments points to low rainfall and high evaporation, when found in veins it is evidence for the passage of saline groundwater, in hot spring deposits to groundwater saturated in oxidised sulphur.

Gypsum crystals on the shore of Lake Tyrrell, Australia

The Jurassic and Cretaceous sediments (200-100 million years in age) that comprise geological succession near the Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS) near Hanksville, Utah contains many different styles of gypsum. The prevalence of the mineral reflects the hot dry climate of the time and evaporation in coastal lakes, lagoons, and inter-tidal flats. The oldest is found in the Carmel Formation, which has thick-bedded gypsum deposited coastal lagoons. This formation crops out near Goblin Valley, familiar to people who have seen Galaxy Quest. It has received almost no study by previous crews at MDRS. The Mars 160 team plans to change that!

Well-bedded gypsum-rich sediments of the Jurassic Summerville Formation exposed near Hanksville, Utah

Closer to the MDRS and higher in the succession (which makes it somewhat younger) is the Summerville Formation. The thin horizontal bedding of brown, cream, white and grey of this Formation is familiar to anyone who has done a rotation at MDRS. Gypsum in The Summerville Formation occurs as scattered crystals and large nodules that crew in intertidal mud and sand flats. Much later, percolating groundwater flowing through fractures dissolved some of the gypsum and then redeposited it as veins. These veins can be both parallel to bedding and cut it at a steep angle.

Close up of the gypsum-rich beds of the Summerville Formation. The lighter the colour the more gypsum is present in the rock. Cross-cutting gypsum veins are also visible

Still higher in the succession is the Cretaceous Mancos Shale. This is a dark grey rock unit, full of organic material and the iron sulphide mineral pyrite. Fossils show that it was deposited in a deep water marine environment. But gypsum is common in outcrop, which is apparently contradictory –why is a gypsum, which forms in water of twice seawater salinity, common in a rock that we know from fossils was deposited under normal marine conditions?

The answer is that the gypsum has formed much later. Oxygen-rich water percolating through the shale has weathered the pyrite, forming sulphuric acid. This has reacted with calcium carbonate of the fossils, forming brines which have precipitated clear sheets of gypsum in near surface fractures in the weathered shale.

Clear veins of gypsum formed by weathering of the Cretaceous Mancos Shale

Gypsum has great potential importance to astrobiology and astrogeology. Understanding the occurrence of gypsum can tell us a great deal about the surface environments on an area, both during deposition and weathering. Furthermore although gypsum, like other salts, is soluble, is also very impermeable. Organic molecules and entire microorganisms can be trapped during the formation of salts such as gypsum and can be preserved for hundreds of millions of years. In the second phase of the expedition the crew will endeavour to visit and sample the much thicker and much older gypsum deposits of Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic.

Gypsum vein on the rim of Endeavour crater on Mars imaged by the Opportunity rover mission (NASA)

Gypsum on Mars

How does this help us understand Mars? Mars is a salty planet, different salts occur as rock coatings, in the soil, as thick deposits, and as veins. These salts include gypsum. The mineral has been detected by remote sensing from orbit and by rover missions on the surface. As on Earth the distribution of gypsum can tell us much about the history of the surface of Mars and of the presence and movement of water on the surface and in the subsurface.

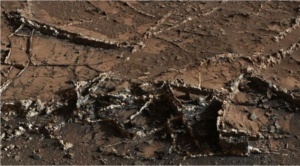

Crystal impressions of salt minerals, probably gypsum, in Gale Crate (NASA)

Bedded gypsum crystals and gypsum veins in fractured bedrock have been observed by scientists of the Curiosity rover mission in Gale crater, supporting the idea that the Crater was once the location of a large lake that later evaporated, leaving behind deposits of gypsum-bearing sediments.

Gypsum veins in fractured bedrock in Gale Crater (NASA)