Sol Journal – December 3rd

It is all about science

I’m not a scientist, but my favorite spot at Mars Desert Research Station is the science laboratory. It was build this summer and sometimes you can still sense little bit of paint smell. The dome has the biggest window in rectangular form, which opens the view to unique Utah desert landscape. This is the place where magic happens – the science discoveries and failures. Mars 160 mission has the main slant in field science research. Shannon Rupert, our Principal Investigator and backup crew biologist, along with members of our Earth-based science team from NASA’s Ames Research Center and Canadian Museum of Nature designed three science projects for our crew astrobiologist/microbiologist Anushree Srivastava. She works closely with crew geologist Jon Clarke. Together they represent the geo-microbiology, which is the study of living and fossilized organisms in interaction with rocks. In order to lightened the heavy science research weight on Jon’s and Anushree’s shoulders, several of us were cross trained for the sampling and work in the laboratory. For me this was great opportunity to dive into microbiology world, even though I’m so far from understanding of it.

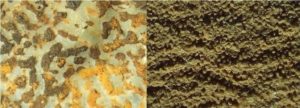

The first research is the mapping of biodiversity and distribution of lichens in this Martian analogue environment. Lichens are composite organisms made of fungi and algae, which usually form a colony. They can be found on the rocks and woody surfaces. If you see on a rocks a different colored patterns that might be lichen colonies. Why we are interested in studying lichens in this Martian analogue environment is because they can sustain in extreme conditions. Previous studies on lichens have demonstrated that they can survive in high radiation and desiccation. On Mars the radiation exposure on the surface is 30 μSv per hour during solar minimum. By studying the maximum constrains of where lichens can live, we can understand if they could survive in space environment. Additionally, they are useful to study the diversity of extreme life on Earth.

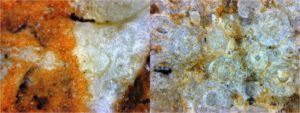

The second is the study of hypoliths, which are photosynthetic organisms that lives underneath translucent rocks in climatically extreme places, just like outside our station. Rock protects hypoliths from harsh ultraviolet radiation, dessication, and extreme temperatures. The rocks are generally translucent which allow hypoliths to receive light and moisture from the soil underside. There is a big possibility to find microorganisms living underneath the Martian rocks. Hypoliths will help humans to understand how to investigate microbial responses to environmental stressors.

The third study is finding traces of microlife trapped in ancient evaporites such as gypsum. Those microorganisms are halophiles. Halophiles (in Greek word for “salt-loving”) are organisms that thrive in high salt concentrations. They can be found anywhere with a concentration of salt five times greater than the salt concentration of the ocean. On Mars are plenty of gypsum deposits and the chances of finding microorganisms in it are high.

I just came back from science laboratory, where the magic was happening. Today Anushree did the plating to grow halophiles from soil samples collected during the EVA’s. But tomorrow will start the routine, observing everyday if there is any growth of microorganisms. It might take 15 days or months, but to be a scientist you have to be patient. And even more patient in the future when humans step on the red planet and the search for life on Mars or its traces starts.