Science Report – October 18th

RECONSTRUCTING SEDIMENTARY PROCESSES ON EARTH AND MARS

Jonathan Clarke

The sedimentary rocks that surround MDRS are full of clues to their deposition, written in a language that geologists can understand. Similar rocks on Mars are written in the same language, or one very closely related. Understanding the language of rocks is what field geology on Earth, Mars, and indeed any other body in the solar system, is all about. So come with me on a journey exploring the literature of rocks, as they pertain to the deposition of fluvial sediments, that this, those laid down by ancient rivers.

It is sometimes said that “The present is the key to the past”. It would be better to say that the present is a yardstick against which the past can be compared. So let’s start with a modern terrestrial river, the Darling River in Australia.

Channel of the Darling River

Our first photo is an early morning helicopter view of the Darling River near the small town of Menindee. The channel is sinuous and has a sandy bed beneath the cappuccino-coloured water, which is full of suspended clays. On either side is the flood plain, composed to clay. Our second photo is of another aerial view not far from the first. This time the Darling is in flood, and the river water has spilled across the floodplain. Sand will be moving down the channel which where the it is flowing fast, and clays will be being deposited on the floodplain where the water is almost stagnant.

Darling River in flood

Our third photo shows the edge of a channel near MDRS. White sandstone of a channel is in sharp contact with reddish-brown clays of the floodplain. The contact between the two is the former river bank. If you cut a section across the channel and floodplain of the Darling with an excavator when the river was dry (which happens every few years), you would see something very much like this.

Cut through a Jurassic-aged channel at MDRS

It’s possible to see the way sand moves along the Darling (and other rivers) when they are low. Moderately fast flowing water moves sand as waves or underwater dunes. Small examples from the bed of the Darling are shown in the fourth photo. Slower moving sand is deposited in ripples, structures that should be familiar to anyone who has been to a beach, be it on the coast, at a lake, or along a river. Darling River ripples exposed by low water are shown in the fifth photo.

Sand waves on bed of Darling River

Sand ripples on bed of Darling River

Cross bedding from former sand waves (photo 6) and cross lamination from former ripples are common in the Jurassic fluvial succession round MDRS. Cross lamination is also present in the floodplain sediments of the Jurassic as well (photo 7) where sandy sediments have spilled out from breached natural river bank levees and depositing thin beds of sandstone.

Cross bedded sandstone near MDRS

Cross laminated sandstone near MDRS

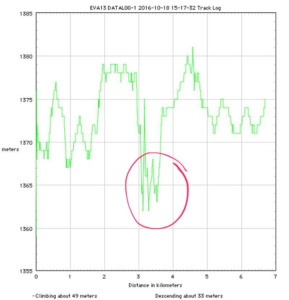

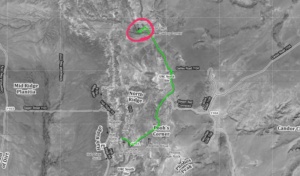

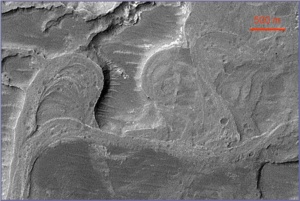

What about on Mars? There are channels at all scales on Mars, from ones much larger than any we see on Earth to small ones associated with gullies that are the same size as terrestrial examples. Many of these channels, although not all, were probably formed by flowing water at some time in the martian past. We know this because we find evidence for the same sort of processes as we see in terrestrial fluvial deposits. Photo 8 shows inverted and exhumed river channels in Eberswalde crater on Mars. These channels were formed in a delta and the migrating meanders of the channel form the same patterns as we see in terrestrial meandering channels. Cross bedding has been seen in fluvial sediments at Gale Crater by the Curiosity rover mission Photo 9, and at Erebus crater by the Opportunity mission (Photo 10).

Exhumed and inverted channels in Eberswalde Crater, Mars (MSSS/NASA image)

Cross bedded sandstone in “Shaler” outcrop, Gale Crater, Mars (NASA/JPL)

Cross laminated sandstone near Erebus crater, Meridiani, Mars (NASA/JPL)

Understanding sedimentary structures as seen in modern rivers are not only the key to the terrestrial past, but to the martian past as well. They provide a yardstick against which we can compare past martian processes with those of the terrestrial past and present. We see these features at various scales from high resolution satellite imagery to ground images of outcrops captured by surface rovers. This way, one outcrop at a time, we build up a history of Mars.