A LANDSCAPE TURNING ITSELF UPSIDE DOWN

Jonathan Clarke

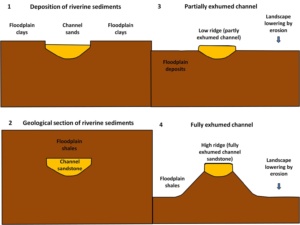

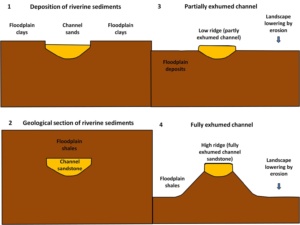

Cartoon showing channel formation, exhumation, and inversion

I have previously described the process of relief inversion and channel exhumation that dominates the landscape surrounding MDRS. In this post I will illustrate the process further. Figure 1 shows how the process works in cartoon form. First we have a river depositing sand in a channel and clays on the floodplain. This was the landscape of this part of Utah in the Jurassic. There were many such channels draining to the north east. Second we have the channel sands completely buried by the clays, the channel sands are then lithified (turned to rock), forming sandstone, and the floodplain clays , which lithify to shales. The sediments are uplifted and then eroded. Third, as erosion excavates down through the sedimentary sucession, the channel is exposed. Because the sandstone is more resistant to erosion than the shales it starts to form a ridge. Fourth, erosion has continued to such a degree that the channel now forms of shale ridge capped by sandstone.

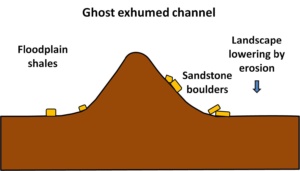

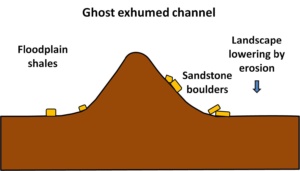

Cartoon cross section through a ghost exhumed channel

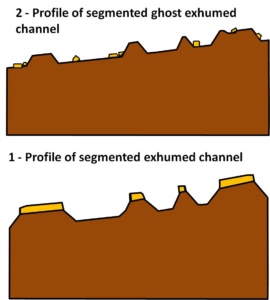

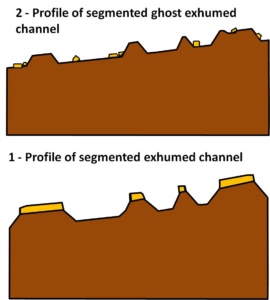

Erosion continues, eventually the sandstone cap becomes so reduced in size that it topples down the side of the shale beneath. This we could call a ghost exhumed channel. The channel has gone, but the imprint of it remains. With the protective cap gone the shale ridge will rapidly (geologically speaking) disappear. Exhumed and ghost exhumed channels are often broken up into segments as streams erode through them. This is shown in the following profiles.

Cartoon profiles along segmented exhumed and ghost exhumed channels

We can see all stages of this process, one by which the landscape is continuously turning itself upside down compared to the original depositional surface. This is because there are many channels at different levels throughout the Jurassic sediments at MDRS. Figure 4 shows a channel that is just starting to be exhumed. Low sandstone outcrops stand just above the surrounding surface of mostly shale.

The next two photos show “Kissing Camel Ridge”, a local landmark. This is the most prominent exhumed and inverted channel at MDRS. It is formed by a large, sinuous channel of very coarse sandstone to conglomerate. The conglomerate at the western end (Figure 5) is still present forming the resistant cap. Further east the channel has become segmented and the cap more eroded, transitioning from an exhumed inverted channel to a ghost inverted channel (Figure 6).

The final stage of the process is the more or less isolated beehive-shaped shale that dot the landscape (Figure 7), and so puzzled me the first time I visited MDRS. It has taken me four visits to work out these details!

The landscape of Mars contains many details that are still poorly understood. Iinvestigation of which will shed many insights into past and present martian processes, hold clues to habitability, and point to potential resources. Examples include the “spiders” of the southern polar regions, the gullies found in many craters, and the “recurring slope lineae” which may be formed by seeping water, but then again, may not. Successful though they have been, robotic rover missions can only scout the surface. As an example the entire traverse of the Spirit rover mission at Gusev Crater, or the distance covered by the Curiosity rover mission to date, could be contained in the immediate area north and south of MDRS. We can cover the distances that took these missions many laborious years to cross in an hour’s driving on our quad bikes, as well as access areas – such as the tops of ridges – that a robotic rover mission cannot.